Welcome to The Ink.

Here we go again… If you’re an American citizen, please exercise your right to vote!

Recently on The Squid

by James O. — I talk to Billy Mavreas—artist, collector, zine-maker, father and life-long Montrealer—about his identity as an artist, the changing Mile End neighbourhood, and the ways in which stuff can both enrich and burden our lives.

🇺🇸 2024 U.S. Presidential Election Special:

James reacts to the onslaught of elections past and present.

Julian revisits the Electoral College, and a scheme to kill it.

Roman imagines the worst and offers reasons for hope.

And Peter talks about the fundamental flaw with third-party candidates.

Please - no more, America.

James: Hello, Ink readers. I have been obsessively reading news articles for the past month. I have read analyses of every angle on how today is going to unfold. I have looked into the 21 micro communities that have outsized roles in deciding the national election. I have watched the analysis of a man who has accurately predicted the last 10 elections (except Gore/Bush in 2000). I’ve followed the polls whose predictions are increasingly more opaque and confusing. Frankly, I’ve made myself crazy and I’m sick of it. We need more psychics, not journalists. So rather than give you a list of articles that will also make you crazy, I’m going to write about how I feel. Maybe this will resonate with you. Likely not. But who knows! It’s the Internet and we’re all entitled to a venue to spew our political craziness!

I am 24 years old this time around. Almost half of my life has been a “will he/won’t he” with Donald Trump.

I remember very poignantly in 2016 when I went to bed the night of election day after watching the votes roll in on the news with my parents. I had school the next day and called it quits after midnight. My dad shook me gently at 6:30am to get ready for school the next morning. “Who won, Dad?” I asked while jolting awake. “You don’t want to know…” was all he said. I remember going to school and all the kids were profoundly depressed. In almost every class, teachers had their heads down as they forwent their planned lessons and held discussions instead.

Fast forward four years, I am 20. I am sitting at my friends Peter and Roman’s (maybe you’ve heard of them?) house during the pandemic. We sat on their couch and watched on their projector the votes be counted. In delirium, I remember laying on their couch into the early hours of the next morning as we listened to Brian Eno’s Discreet Music on their speakers while we watched the muted projections. Head in hands, how could it be this close? We went out into the foggy November night and tried to shake out the creeping feeling of election insanity. At one point, Peter ran off into the dark woods of Mount Royal, leaving Roman, Julian and I in the park. For the next week, I compulsively checked my phone for updates from The New York Times declaring a winner. No dice. My hangouts with friends would consist of us getting coffee (to go, sometimes wearing masks outside) as we walked around in the November cold, not talking, checking our phones. Biden was announced the winner. Everyone I knew had a collective sigh.

Now here we are. Round three.

I said I would write about how I feel about this election. I feel anxious like most people. I feel tired. I’m just exasperated, wanting to scream “HOW DID WE EVER LET OURSELVES GET HERE?” Feelings that are familiar and not that profound. Just another election year I guess.

Whichever way the results will go, it’ll take a while for us to know. Exactly half of the country is going to be mad. And regardless of how it happens, it’s going to be messy. Who knows—if Trump loses he’ll only be 78. If he’s not in jail by 2028, he can run again at 82. Wahoo. Or maybe one of his nutcase children can take on the family MAGA business. Barron, maybe? I don’t know what’ll happen. All these journalists don’t. Election predictors don’t. Even psychics probably don’t. The only thing I know is that it’ll be surreal, and maybe it only gets more surreal from here. As the Grateful Dead sang, “What a long, strange trip it's been.”

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

Julian: Yet again, it feels very possible that the winner of today’s U.S. presidential election might lose the national popular vote, and perhaps by a significant margin. I want to briefly revisit the Electoral College system that makes this quirk of American democracy possible, and in particular a novel plan to circumvent it in the future.

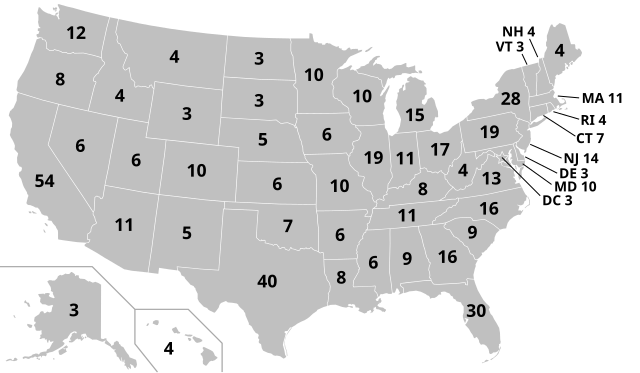

As you probably know by now, American voters do not elect their president directly. Instead, voters in each state are actually nominating their state’s share of some 538 electors who will be sent to the Electoral College, with the Electoral College in turn ultimately electing the president.

Each state legislates exactly how they will select their electors, but in almost every state, the candidate who wins the majority or plurality of the popular vote in that state will receive 100% of the state's electors. For example, if Kamala Harris wins the most votes in Colorado, a state with 10 Electoral College votes, all 10 electors sent by Colorado will have pledged to vote for Kamala Harris in the Electoral College—even if Harris only won the election in Colorado by a single vote.

There are 538 votes in the Electoral College, and the president is elected by simple majority, meaning that the person receiving at least 270 Electoral College votes is elected president.

This convoluted system has become increasingly controversial in recent years, as both the 2000 and 2016 presidential elections were won by the runner-up in the national popular vote: In other words, the person with a greater share of the popular vote lost. It also means that a very small pool of voters in certain swing states have the power to tip their state’s popular vote, determining a potentially large number of Electoral College votes, and thus, the result of a presidential election.

Furthermore, the Electoral College was at the centre of one of Donald Trump’s schemes to steal the 2020 election—by trying to get Mike Pence, in his role as Vice President, to illegitimately reject legally-appointed electors from swing states that had voted for Joe Biden, and have them replaced by loyalists who would instead cast their Electoral College votes for Trump. Thankfully this did not happen, but only because Mike Pence suddenly grew a spine after four grueling years of enabling Trump; J.D. Vance has made clear that he would gladly try to exploit the Electoral College to steal an election.

All this to say, the Electoral College not only produces results that can feel highly opaque and undemocratic, but also leaves far too much room for shenanigans and meddling.

But there is a plan underway that seeks to use the Electoral College system against itself by exploiting these very weaknesses in the name of establishing a national popular vote.

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement between a number of states and D.C. that would change the way that participating states assign their Electoral College votes. States in the compact would assign their electors to the winner of the national popular vote, regardless of the winner of the popular vote in that state.

Again taking the example of Colorado, this means that in the event that Kamala Harris won the national popular vote, Colorado would still send all 10 of its electors to vote for Harris in the Electoral College, even if Donald Trump happened to carry the popular vote in the state itself.

The interesting thing about the NPVIC is that all 50 states need not participate. The NPVIC becomes decisive once the members of the compact together represent at least 270 Electoral College votes. That is, when a majority of electors in the Electoral College are voting for the winner of the national popular vote, it doesn’t matter how the remaining states’ electors vote: The winner of the national popular vote will always win a majority in the Electoral College.

Because the U.S. Constitution simply requires that a state appoint electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct”, proponents of the NPVIC argue that such a method of assigning electors is just as legal and legitimate as the current winner-takes-all method most states have enacted.

This may sound like a far-fetched scheme. In reality, the NPVIC has already been adopted by 17 states and D.C., together representing 209 votes (38.8%) in the Electoral College. Another four states have bills pending that would see them join, together representing another 50 votes (9.3%). The compact automatically takes effect once the threshold of 50% + 1, or 270 votes, is reached.

While not a sure thing, the NPVIC is not some impossible fantasy either. It is highly plausible that more states will join the NPVIC, and it could take effect in the coming years—especially if today’s election produces a controversial result with the Electoral College at its epicentre.

A constitutional amendment changing the way presidents are elected is practically inconceivable. Given this reality, the NPVIC seems like the most probable path to a national popular vote in the United States. But even if the compact ever does take effect, don’t expect it to be smooth sailing. There will inevitably be an onslaught of legal and constitutional challenges launched by those who question the compact or otherwise seek to maintain the status quo.

Ultimately, I think the NPVIC further demonstrates how broken the Electoral College really is. The compact seeks to improve the legitimacy and straightforwardness of American elections in a way that itself feels devious and undemocratic. While the NPVIC may be an interesting experiment in the malleability of the American system, in practice it’s yet another exploit to which the Electoral College is vulnerable—it just so happens to be a means to an end that I agree with.

I hope that, after today at least, the Electoral College produces a result that reflects the will of the American people, instead of further stoking resentment and confusion at a time when such sentiments can scarcely be afforded.

If Trump Wins, Take Comfort in the Following:

Roman: It’s Election Day in America, and if you’re anything like me, you’re anxious and dreading a very plausible Trump victory. The stakes in this election, like in the past two elections, feel staggeringly high. A victory for Trump could have grave consequences for a laundry list of critical issues both in the United States and globally: from abortion rights to climate change, the war in Ukraine to the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, immigration to the existence of democracy itself.

Given the circumstances, it’s easy to despair at the possibility of a second Trump presidency. But that would be a mistake - there are genuine reasons to stay hopeful, even if Trump wins. Here are some worth considering:

The United States Congress

We don’t know yet who will control Congress in the event of a Trump victory. Republicans seem all but certain to win control of the Senate, but control of the House is uncertain. In any case, the Republicans will not have a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate. This would limit a hypothetical Trump administration’s legislative agenda to bills passed through budget reconciliation, which can only be used once a year. And even a Republican-controlled House could be a moderating force on Trump’s worst instincts: for every MAGA-loving Republican, there’s plenty of more moderate, centrist Republicans from swing districts who might oppose bills introduced by Trump’s team.

2026 midterm elections

There’s another major election in two years. 33 Senate seats and all 435 House seats are up for grabs, and, if history is any indication, Democrats would have a major advantage if Trump is in the White House. In 2018, two years after Trump’s stunning (and galvanizing) 2016 victory over Hillary Clinton, Democrats swept the House in a “blue wave,” gaining 40 seats and decisive control of the chamber. A repeat in 2026 would effectively halt any Republican legislation from getting to Trump’s desk.

The courts

The United States has a robust, independent and powerful judiciary, with a balanced mix of federal judges appointed by Democrats and Republicans. The US judiciary system is by no means perfect, but it’s generally free of corruption and not beholden to Trump or the Republican Party. Just look at Trump’s attempts to overturn election results in 2020: in case after case, judges – including many appointed by Trump himself – repeatedly ruled against lawsuits challenging the election results. Rest assured: any future attempts by Trump to enact controversial parts of his agenda, or to break the law, are almost certain to be met by a wave of lawsuits.

Trump himself

Let’s face it. Trump isn’t a particularly smart or cunning political operator. He’s a good campaigner, undoubtedly, and incredibly politically resilient, but he’s not very good at getting his agenda passed when he’s in office. He failed to repeal Obamacare. He mostly failed to get his border wall built. He failed to get any kind of infrastructure bill passed. The guy just isn’t a Putin-like Machiavellian genius who can persuade the public and negotiate with Democrats to get his extreme agenda passed. In fact, it’s quite the opposite: Trump is really good at riling up intense opposition to his agenda and administration. A more diplomatic and disciplined Republican in the White House, though more palatable on the surface, would almost certainly do more legislative damage to the country than the toddler-like Trump (that was the fear with Ron DeSantis, for example).

But, but, but:

Each of these reasons for optimism has its flaws, of course. Trump could enact large parts of his agenda and deal incredible damage without going through Congress; the Republicans could keep (or win back) control of Congress in the midterms; the courts have ruled against Trump, but they’ve also given him norm-shattering victories; Trump isn’t a modern-day Machiavelli, but his team is laser-focused, aggressive, and ambitious. We should not, I repeat, we should not be complacent. But we shouldn’t give up hope, either.

Fingers crossed.

Third-Party Presidential Campaigns are Fundamentally Flawed

Peter: At this point we’ve been hearing it for years — the presidential election is a choice between “a giant douche and a turd sandwich”. With 28% of voters expressing a dislike of both parties, Americans are increasingly dissatisfied with the two-party system, and independent voters now make up 43% of registered voters, dwarfing the shares of each of the two main parties. With all this third-party sentiment brewing in 2016, the Libertarian party, a popular choice with Never Trumpers got… 3% of the vote. In 2020, amid a more concerted effort to counter Trump, their share was even less (but hey, Kanye’s Birthday Party got 0.04%).

Why are third-party presidential candidates such a joke? There are rational arguments against third-party voting that Americans know well; most famously, the spoiler effect, whereby a vote for a long-shot third-party candidate, perhaps further to left or right of a mainstream party, ends up helping the mainstream candidate on the other side of the spectrum, thus producing the opposite outcome to what the voter intended. There is also a tacit acceptance of Duverger’s Law, which states that party systems are by and large determined by electoral processes (in other words, the first-past-the-post Electoral College nightmare Julian describes makes the two-party system inevitable). Proponents of third-party voting will also point to the legal maze both parties have constructed to make it incredibly difficult to get on the ballot in all states, and the enormous amounts of money that pour into GOP and Democrat coffers.

But say some of the 39% of Americans who expressed strong desire for more political parties in the U.S. banded together into a credible third-party, something that goes even beyond Ross Perot’s tantalizingly close independent campaign of 1992; a real, institutionalized party. If we settled into this three-party system, with one coalition getting around 35-40% of the popular vote and taking office, wouldn’t that be… undeniably worse? Not only would an even greater majority of the electorate have their vote not represented, but imagine the insane gridlock that might descend upon the US congress if the Executive, Senate, and House all represented differing pluralities.

But wait, you say, obviously electoral reform would be needed. That’s what Duverger’s Law is all about. And sure, if the U.S. implemented a run-off ballot system similar to France, and abolished the Senate, introduced a prime minister to the House of Representatives, and vastly reformed campaign finance law for good measure, then a third-party president would be viable. As we all know, these things will never come to pass (take it from a Canadian, elected officials are rather indisposed to passing electoral reform that won’t help them win re-election). So to be perfectly clear: any third-party campaign for president in the United States is built on a fundamental lie about how the existing American political system is designed and functions. It’s not only that they won’t win; it would be a bad idea if they did.

I say president, in italics, because I do believe there is a strong opportunity in the American system for third party voting when it comes to congressional bodies. There is endless historical precedent for third-party representation in state congresses. There are even examples at the national level, with Minnesota’s Farmer-Labor gaining a foothold in Congress in the 1920s and 1930s. To me this speaks to the true power of third parties, which is not in governing but in coalition-building. Third parties often represent niche or regional interests that speak to the needs of the few over the many. In a representative context, that’s a good thing! Voters in a representative democracy should be empowered to vote for the candidate that maximally represents their interests, and the congressional system should encourage coalition-based decisions that represent the views of a majority on each issue. Take the Canadian example — while the NDP have never formed government, they have had a huge impact on our politics and policy, most recently leveraging their supply-and-confidence deal with the Liberals to get a vast progressive policy agenda accomplished in exchange for keeping Trudeau in power.

In the presidency, on the other hand, there can be no coalition-building. One candidate wins. Tyranny of the majority. Indeed, the French system, probably the best model America can look to for electing a head of state, demonstrates this: run-off ballots are not proportional representation, and tend to skew towards a middle-of-the-road candidate that a minority of voters would have selected as their first choice, but most are at least okay with — in other words, the least bad option. In a context where inter-party coalition is structurally impossible, the only lever Americans have to influence the direction of the executive is intra-party coalition. By joining political parties, getting involved in party processes, and leveraging split tickets and third-parties in congressional races to influence party governance and policy, Americans could have a tangible effect on the options available to them for president. Put it this way: in a context where nearly half of registered voters aren’t a member of either party, is it any wonder that the candidates fielded by those parties don’t represent the views of most voters?

Americans often overestimate the power of the presidency over their lives and underestimate that of local and state officials — a misconception that isn’t helped by a media that discusses “Trump’s economy” or “Biden’s migrant crisis” as if these phenomena are attributable to these individual men rather than cascading, decades-long, complex processes. By putting so much stake into the presidency, I think they also are prone to misunderstand what the president is supposed to be. The president doesn’t represent your views. They represent the majority. Voters choose the least bad option, because that’s what the president is supposed to be. It is the delicate interface of this tyranny of the majority with the representative democracy of Congress that is meant to be the “beauty” of the American system. Obviously, it isn’t working that well. But if Americans want it to work better, they would be better off voting for third-party congressional candidates and getting involved in party politics, than giving up and electing Kanye president.

Great reading, and thanks for offering reasons for hope, too.

Such thoughtful analysis from all the Squid contrbutirs, but what is really affecting me this morning is James's account of the last two elections snd the photo of Roman listening in dread to the early 2020 results.